One of the “25 lessons” I presented at LoopConf this year was “Software can be finished”.

I tried to remove this lesson from the talk to make room for something else. But it kinda took on a life of its own and wanted to be in the talk. It was an Important Lesson.

“Software can be finished” is a controversial statement. And I want to be clear, as I was in the talk, that in many cases “finished” software is not, and should not be, the goal.

But I present it as an idea. An ideal. A theory. Something to chew on and think about.

What would finished software be like? How would we write it? And what can we learn about the way that we create software by considering these other questions?

What is software?

“Software” is actually quite a broad term, spanning everything from low-level firmware running on devices; operating systems; command-line tools that only developers use; compiled code that runs on its own; interpreted code that needs some other piece of software – or even an entire other application like a web browser! – to run it.

Software takes many, many forms, and is created and executed in many different ways for many different purposes.

What is “finished”?

For the purposes of this article, for software to be “finished” I’m going to say that:

- It is feature complete. New things can be added, but do not need to be added. It “works”. It does something useful as it is.

- It is secure – We understand enough about it to be able to say that it will not need to be updated in the future to patch security vulnerabilities.

- It is standalone. My meaning of this is quite specific, it means that it has no runtime dependencies except for an interpreter if required.

There are some implications of building to this definition of “finished”:

- If hardware, platforms, interpreters, or external APIs change, our software may stop working. This is not within our control though.

- If build tools change, then we may not be able to modify our software. This is also not within our control.

You could say that changing platforms and tooling are the reason software can’t be finished – we need to keep it updated in order for it to work. But perhaps focusing on what we can control is important here.

Perhaps this seems unreasonable? Too limiting? Perhaps you’re thinking that you couldn’t build any substantially sized piece of software that meets this definition.

You’re probably right. In which case, don’t build “finished” software. That’s 100% fine. Many businesses are run on the basis that software updates and fixes will be provided as part of the cost of access to the software. “Finished software” is – in many cases – a bad business model.

(Or is it? I recently heard a less technically inclined person state that: “The thing about software is that you make something once and then you copy it infinity times and you make infinity profit?” – which is a very interesting way of looking at software.)

I keep repeating it, but one more time, before we look at some real examples: This article isn’t saying you should build finished software. It’s saying that thinking about what finished software might be like could hold some interesting lessons for us.

Examples

Example 1: The Nintendo Gameboy

In my LoopConf talk I asked the audience: “What do you think the oldest software I could find in my house is?”

And the answer is, as far as I can tell, the Nintendo Gameboy.

I believe the software in this device (yes, I own an original) is, at the time of writing, 35 years old. It has not been updated. And I’ve never come across any bugs. This is equally true for the games on it.

This is non-trivial software. It’s an operating system! And games! It was not safety-critical or mission-critical. And yet, once it hit the devices and cartridges… that was it. The software was done.

Example 2: Job Sheet Manager

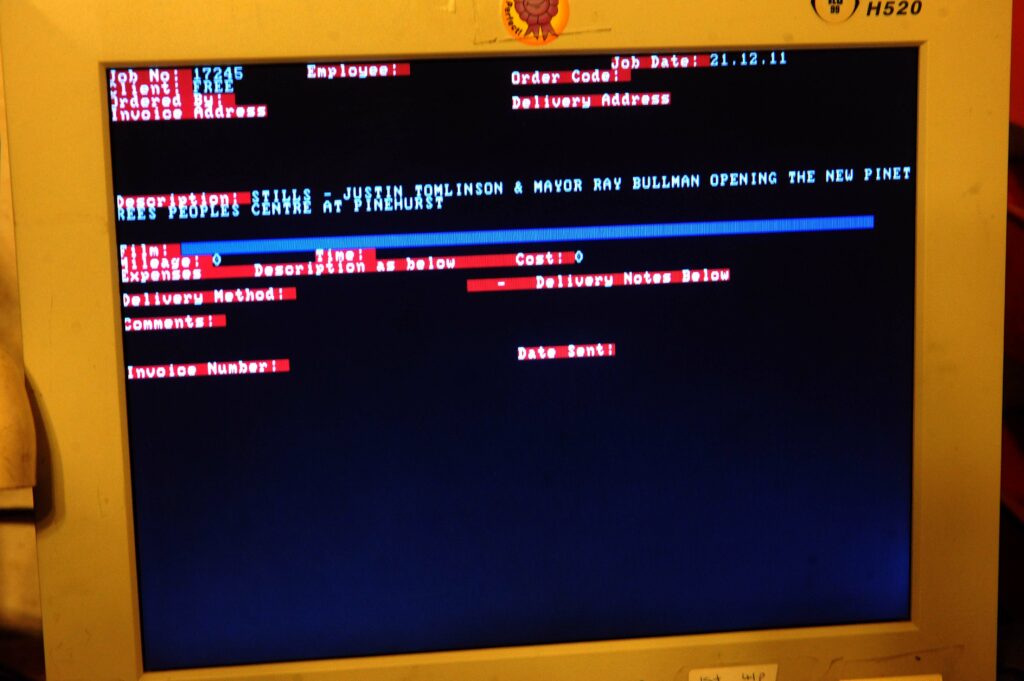

In the UK’s education system we study “A’ Levels” from age 16 to 18. For my A’ Level Computing project in my final year, I built a tool in the Pascal language for my parent’s business.

This tool was really used in a real business.

And sure, the version I wrote for my A’ Levels was not the final version. It was added to a bit in the subsequent years. But at some point I stopped working on it.

That tool was compiled as an x86 (Intel Chip) executable with no dependencies. It used a character-based display. And its own binary file format.

The final entry in the database was added in January 2012 after 17 years of use.

Job Sheet Manager was finished software.

Example 3: A multitude of embedded systems

Many people will have in their homes a washing machine, fridge, freezer, dishwasher, oven, hob, boiler/furnace, air conditioning, thermostat, microwave, toaster, kitchen and bathroom scales and one or many clocks.

Perhaps you have an older, non-connected TV, or DVD player, or music system.

Perhaps you’ve had a pacemaker installed in your chest that will be there, inside your body, for 10 years (actually, I just looked up pacemakers and they can get firmware updates nowadays, which is kinda crazy, so scrub that).

Most of these common electronic household devices/appliances will have software in them. This is “embedded software”. And it’s FREAKING EVERYWHERE!!!! Even if you don’t have a “smart” home.

The things I’ve listed are only the beginning.

If an electronic device is not internet-connected then it’s almost certainly running software that has never been, and never will be, updated. That software is finished.

In one conversation I had about this, my friend said “I’d have to assume its environment never changes (eg the gameboy)”, and they are right. In these cases the software is built for a device, lives with the device, and dies with the device.

But that’s fine. It’s still software (I’m including firmware in my definition). And it’s still finished.

And in any case, even if your environment does change, my point in this article is to get you to think: what if the environment did not change, and I could write finished software. What would that process and end product be like?

Example 4: Some small Javascript apps and libraries

Finally in examples, and bringing it back to my current world of web development, I have created a large number of small web sites, “applications”, and libraries that I consider finished.

Some are more complex, but many of these are relatively small.

I’ve made, for example:

- A serverless two-player Scrabble clone

- A simple notes app

- A helpful PHP reference tool

- A choice-driven chabot library in just over 100 lines of vanilla JavaScript

I’d argue that their small-ness and simplicity is actually one of the things that “finished” drives you towards.

If you know you’re going to only work on a project for a limited time, but that you want it to continue working without maintenance, you keep the scope small (see Peekobot), you fight to remove infrastructure (see Untitled Word Game), you… OK, too many spoilers.

Let’s look at what the considerations/simplifications are. What does finished software look like and what thinking goes into it that we can learn from?

How to make finished software?

This will be an incomplete list, and I encourage you to think it through yourself, after reminding yourself of the definition of “finished” that I gave earlier. What would you add? What is unreasonable?

I note that I don’t have any kind of formal process for all of this – most of my “finished” software is side projects where I’m working alone and fairly chaotically. So these are just ideas about what could go into “finished” software.

1. Understand the requirements

Think hard up front about what you are going to do and how.

Ask as many questions as you can before you begin. Document this as you go.

One output of this part of the process might be that you decide to build a very different product. Or not build a software product at all!

You will already be thinking about the other limitations of your project here. This is good.

2. Keep scope small and fixed

This will closely relate to the requirements. But the idea here is that embracing constraints can lead to creativity.

The Gameboy had 4 shades of grey and very limited memory and processing power, but the games on it were still great.

My Peekobot chatbot is choice-based, not using AI or text analysis algorithms.

My Scrabble Clone has no server, so the game data goes in URLs. (It’s interesting seeing other tools like this calendar putting data in encoded URLs).

Most embedded systems have very limited functionality derived from their fixed user interfaces and available hardware.

Challenge yourself on simplicity here.

3. Reduce dependencies

Dependencies are hard.

And they are in different places:

- Build dependencies. These don’t matter so much as long as you can accept that you may not be able to re-build the software at some future point.

- Runtime dependencies. Try to avoid them (see “Produce static output”, below). Some examples from web-development:

- You can avoid lpad-style issues by copying and pasting simple libraries into your project (as long as you underderstand them).

- You can download external libraries and host them yourself instead of relying on CDNs.

- You can use progressive enhancement.

- You can code defensively and fail gracefully when external APIs break or go away.

- Platform dependencies. This is harder to deal with and may actually represent a hard constraint. Platforms will change and ultimately, in many cases, break your software. But that’s kinda the point: what is a technology stack that will have the longest lifetime. How does thinking about that affect what you make? For web-based projects, for example, you might need at least consider hosting. What happens if your host disappears? Can you easily re-deploy somewhere else?

4. Produce static output

This is very similar to reducing dependencies. But if you need dependencies, how you can not have a reliance on external services or platforms to provide them?

These things are discussed above in the runtime dependencies point, but can you statically include code in your project if it’s simple and well-understood? Can you use trusted platform features (in my world this is vanilla HTML, CSS and JS) instead of libraries?

5. Increase Quality Assurance

Another of my LoopConf talk’s “Lessons” was “Don’t fix bugs – avoid them!”

What tools and processes can we use to reduce the chance of bugs being in our software in the first place? How do we “move slowly and not have to fix things?”

Linting, static analysis, testing, and quality assurance can all help.

Simple code that’s easy to understand helps.

A good code review process in a team you can trust helps.

And quality is as much about “building the right thing”, as it is about “building the thing right”, so requirements thinking feeds into this too.

Even if you accept that you can’t have zero bugs, what can you do to have fewer bugs?

Summing up

As software developers we should always be on a journey to writing better code, for some definition of “better”.

Programming is engineering, and engineering is about trade-offs. Stronger materials might weigh more or cost more, for example, so you only use them where you really need that extra strength.

My aim here is to give you a different notion of “better” to consider. A different set of trade-offs to think about.

There is a utopia where we write correct, bug-free, fast, secure, statically-built software with zero dependencies that does it’s job and will continue doing it’s job as long as the platform it’s written for endures. This feels like it should be a thing we strive for. It feels like a Good Thing (TM)

As I have said, and as I want to stress again, these might not be the right trade-offs for you, your company, and your product. You’re probably not making a Gameboy, or a dishwasher. Finished software probably isn’t your goal.

But maybe there are ideas here in the concept of finished software that might be new, or that might take on a new importance as you think about this idea.