Technology presents so many opportunities for people to get involved in making public services data. And there are probably challenges too. If only the information was open!!

Recycling data

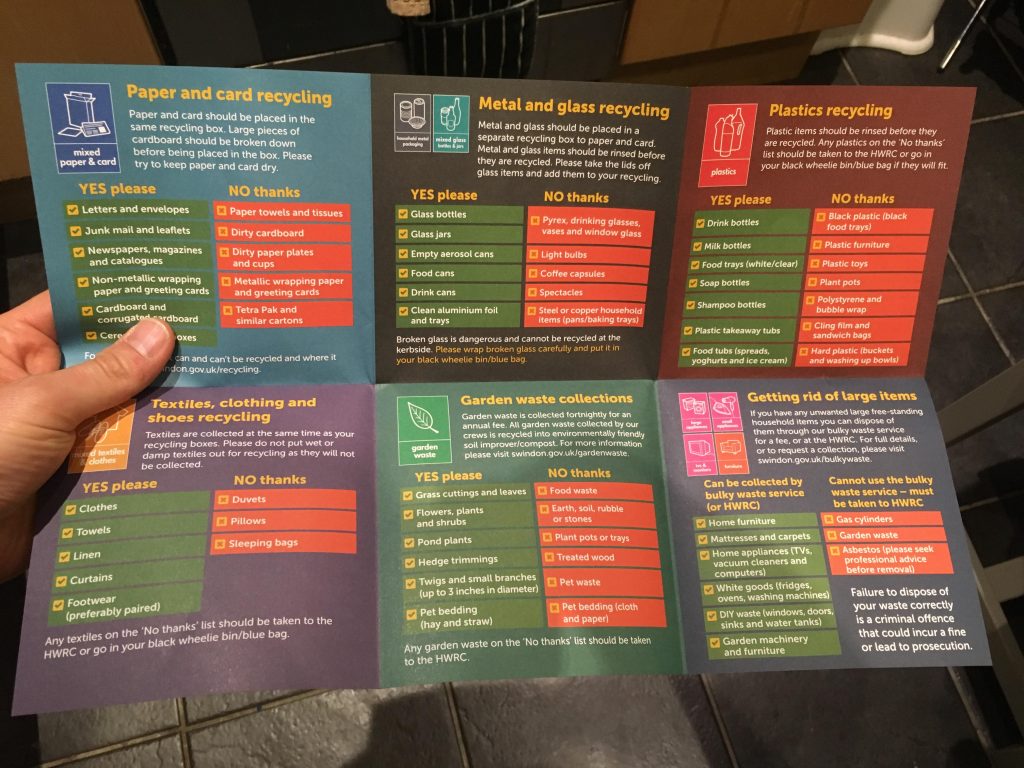

Our council here in Swindon recently changed the recycling rules. To inform people they produced a leaflet explaining which materials should go in which boxes.

Now, I could stick the leaflet on my fridge. But…if I did so there wouldn’t be room for any cute pictures that my kids drew, or of those stupid ClubCard vouchers that I keep forgetting to spend.

It’s HUGE! (I do not have Donald Trump-sized hands!)

When I saw this I immediately thought: wouldn’t it be great if there was a simple app or something where I could search for materials to quickly find out if they are recyclable and which bin/box/bag they should go in.

Apps are generally overkill, but I quickly realised you could do this with a simple piece of JavaScript website code. And that I’d already built a nice filterable list as part of a free coding course that a chap called Wes Bos put together.

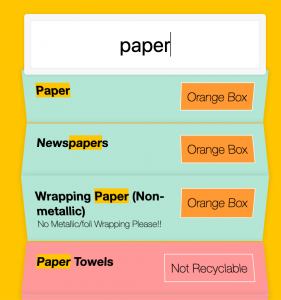

So within about an hour I’d re-cycled the code from the course, tweaked it, and added some of the recycling information to make a quick prototype.

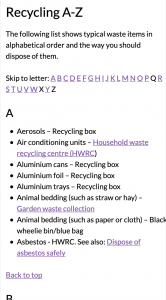

Aside: Having done this, I thought “Oh, maybe the council already have a list like this on their website?”. They do have a full, indexed, A-Z list, but it’s not as good as a filterable one, and adding a filter seems like a relatively simple but very welcome enhancement:

A good citizen?

I did a bit to promote this idea, and it got a little traction and love. My super local councilor, Jim Robbins, did his best to promote it to the powers that be.

And then a few days later a local journalist asked if he could to a story about it to promote it. To which Jim Robbins replied: “Swindon Council should be encouraging great citizen engagement like this”

Now I’m a bit shy, and the local press (not necessarily this specific journalist) doesn’t have a great reputation for presenting things accurately. They can make a story out of nothing sometimes – welcome to local journalism! So I wasn’t sure how this would go down.

But this comment about encouraging citizen engagement was interesting.

One other reason I’m hesitant to have a story about this prototype at this point is that…well…am I ALLOWED to make something like this? The leaflet has no copyright notice on it so it is copyright by default. The website is explicitly copyrighted by the council.

So can I take this data and re-purpose it? Would I be at risk of hindering the council in doing this, for example, if the list got out of date? Would I be at risk of impersonating the council and making something that looks official even though it definitely isn’t?

And yet, in the words of my councillor, making a tool like this is “great citizen engagement”.

Data reuse and recycling

This isn’t the first time I’ve got involved in making tech that aids government and democracy. I made a Petition Tracker that tracks the signatories on government petitions over time. This blew up recently when the “Revoke Article 50 Petition” took off.

I was able to make the Petition Tracker because the government petition data is:

- available in a structured format called JSON that I can process easily with computer code

- “open” – that is, I’m explicitly and freely allowed to use it under a license called the “Open Government License”

This open-data has enabled a whole raft of tools to pop up analysing the petition data in various ways.

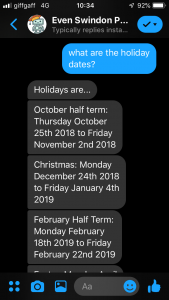

And there are other things I’ve made where I’ve kind-of re-used data where I’m not entirely sure I’m allowed to. My SchoolBot (private access only for now), for example, uses term dates and other information from the council and school websites to make that data more easily accessible through an “intelligent” Facebook messenger “bot”.

And after the huge success of “Beat the Street” in Swindon last year, I made an experimental “virtual” clone of the game, called Zap the Map, that you can play with a smartphone. But was I allowed to copy and use the locations of the “boxes”?

On Innovation

Hold that thought – let’s talk about innovation.

About 18 months ago I attended an “unconference” on the topic of digital tech in charities, where one of the sessions was about innovation.

In this discussion were two general opinions.

- Innovation is hard because it’s expensive and hard to get sign-off for and it’s risky and prone to failure and charities don’t want to waste donors money on it.

- Innovation is easy with modern technology, you can try things out quickly at low cost, fail fast if things don’t work, pick things that work and develop them further and it’s a route to improving all sorts of things. It’s actually riskier to embark on a big, long, time-consuming project with an uncertain outcome.

I admit, the reality is that opinion 1 is probably the most realistic right now, and this was the opinion of most of the people who worked for/in charities in the room.

But technology people prototype ideas and run little side projects all the time and are so used to the way of working outlined in the second opinion. And we see the opportunities that this way of working presents. My list of side projects is testament to this approach.

And – I should add – I don’t believe innovation needs to be purely digital. Heck, even Dyson (still) make cardboard prototypes of things to try them out!

one day I was at a local sawmill and noticed how the sawdust was being removed from the air by large industrial cyclones. My engineering instinct kicked in. Could that work on a smaller scale? So I created a cardboard prototype and strapped it on to my machine. It didn’t look great, but it picked up more dust. Fifteen years and 5,000 prototypes later, I had a bagless vacuum cleaner.

James Dyson in The Guardian

The Opportunities of Innovation

So what if there are some good citizens out there who have interesting ideas about how to use information technology to improve public services, make life better and easier for fellow citizens, help charities and businesses be more effective?

And what if those ideas aren’t being explored because the people who own the data don’t make it available in usable formats, and allow it to be copied and repurposed?

If the data/information/content the council owned was more open, could tech-savvy people like me, who want to improve things for themselves and others, at low cost, be empowered to innovate with digital (and non-digital) technology, and allow the council to take the ideas that look like they are working and move them forward to make official tools?

A closing note on the actual risks and issues

Two more things.

Firstly, I’m sure there are tech teams working on stuff like this for the council. I’m sure they are cash-strapped and have limited remits. But I’m also guessing that they work for huge corporations like Capita. I’m sure that both the local councils and the IT companies that they employ have lots of red-tape and budgetary constraints and so on. I have experienced some of this first hand through the council’s procurement processes.

But I suppose this is my challenge: innovation can’t work within these kinds of processes. A single freelance web developer like me can take what exists and make something better in a very short space of time at very low cost. Are these ideas at least worth exploring somehow? Is it worth having a framework for innovation that allows ideas like this to be evaluated?

Finally, I know this seems like a rosy, utopian view of how local government works or could work. The reality is that you don’t want people taking data and abusing it, masquerading as the authorities and confusing people, profiting unnecessarily from it, or putting unnecessary burden on the authorities. I understand all that. How real are these risks? I don’t know. How can they be managed? I’m not sure.

But I can’t help thinking that good citizens like me with useful skills and ideas are prevented from using those skills for the public good. The Petition Tracker and related tools show how open data can be great. I’d love to see local governments working more like this.